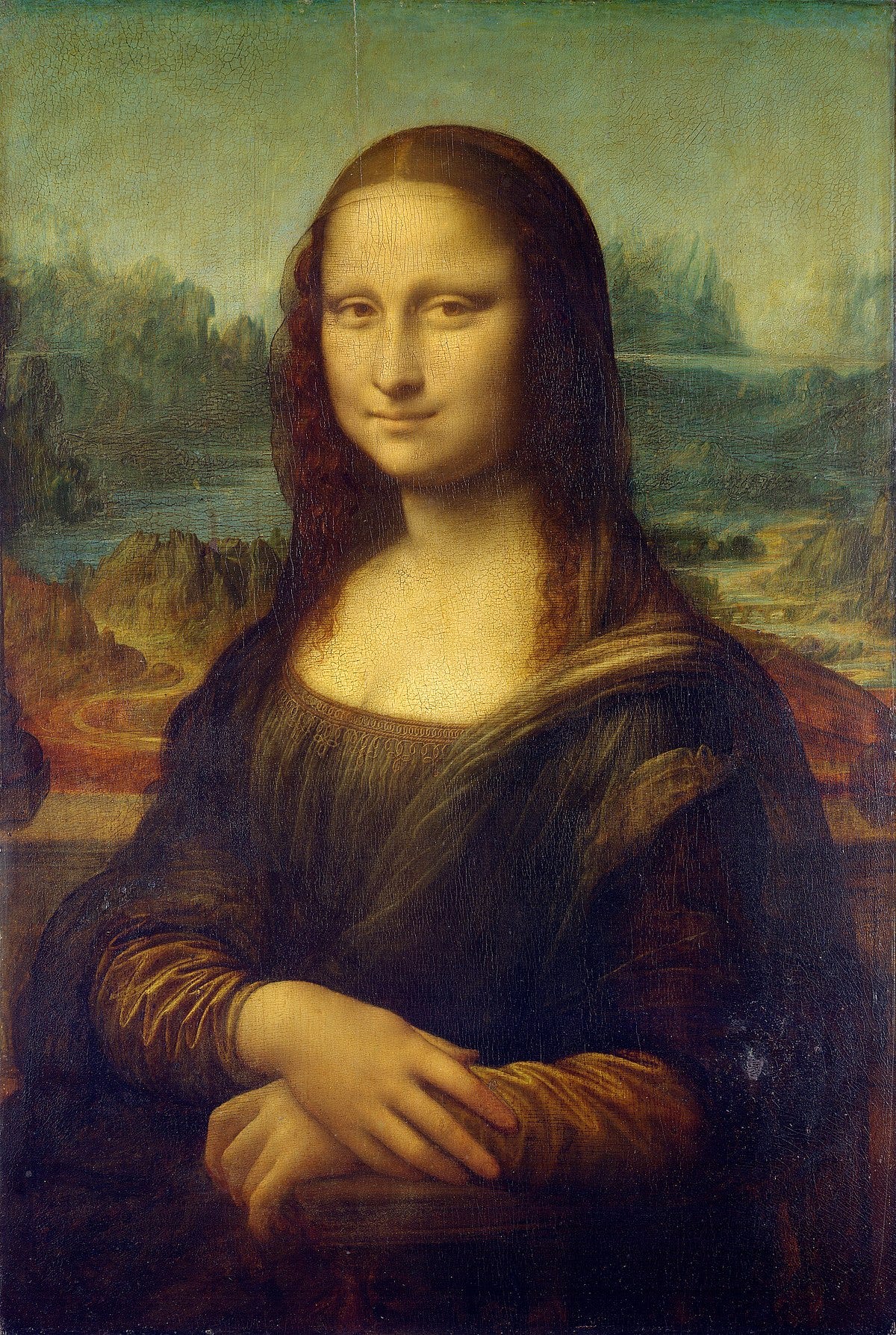

The Mona Lisa in America

How Jacqueline Kennedy managed to pull off the biggest coup in the history of art diplomacy: getting The Mona Lisa on loan.

On January 8th, 1963, a little more than eleven months prior to his death, John F. Kennedy hosted an event at the twenty-two year old National Gallery of Art that was unprecedented in world history. He was unveiling the “Mona Lisa” for its first – and so far only – appearance on American soil. This massive achievement in artistic diplomacy wouldn’t have been possible without the help of First Lady and noted Francophile Jackie Kennedy, who first broached the idea with French Cultural Minister Andre Malraux during his visit to the Gallery a year earlier.

The idea might have had Mrs. Kennedy enthralled, but it was a tough political sell in France. Many Frenchmen believed the painting was uniquely French (even though it was painted by an Italian) and a national symbol, and therefore shouldn’t leave the country.

Others argued that the painting was too delicate for a transatlantic trip. They had a point, considering Da Vinci painted it on a thin poplar board, which made it very sensitive to heat and humidity. But the opportunity to win more favor with the American people was too good to pass up, and Malraux arranged to a loan from the Louvre. When the decision to loan the painting was first reported on December 8th, 1962, it drew mixed reactions.

“Suggestions of the "Mona Lisa’s” temporary departure from France already have caused a stir there,” reported The New York Times. “The French Academy of Fine Arts and other groups have opposed moving the painting from the Louvre. However, authorities at the Paris museum have given the painting a thorough physical examination and announced this week it was fit for travel.

The “Mona Lisa” didn’t fly. It was figured that may have been too hard on the flimsy painting. She was carried across the ocean aboard the Liner France. According to the New York Times, the painting left the Louvre “in a specially designed steel box that will protect the Leonardo Da Vinci masterpiece from shock and changes in humidity and temperature.” The Times also stated that the painting was given a first class cabin with a guard posted outside.

When the "Mona Lisa" arrived in Washington on December 21st, she was in perfect condition. The painting was shown to reporters and photographers from inside her temporary home – the bomb proof, concrete vault known as “Vault X” in the gallery. A reporter described it as looking like “a large cell block in a jail, complete with a catwalk and glaring lights. Even guards weren’t allowed inside with the painting, instead watching it through closed circuit security cameras.

The "Mona Lisa" in America was a massive deal. In fact, she was ready to go on display long before January 8th but, even amid public cries to “Let ‘Mona Lisa’ Out!” the French Government refused to put her on display until the Congress had returned from their recess.

When The "Mona Lisa" was finally let out, it was before a crowd of 2,000 VIPs including Supreme Court Justices and Cabinet Members, as well as the Congress. John F. Kennedy and Malraux both spoke in the cavernous West Statuary Hall of the gallery. They spoke of the relationship the United States and France had forged over the previous half Century, including how the United States was integral in saving France – and by extension, The "Mona Lisa" herself – in World War II (where Kennedy himself served in the Pacific).

Mr. Minister, this painting is the second lady that the people of France have sent to the United States, and though she will not stay with us as long as the Statue of Liberty, our appreciation is equally great. Indeed, this loan is the last in a long series of events which have bound together two nations separated by a wide ocean, but linked in their past to the modern world. Our two nations have fought on the same side in four wars during a span of the last 185 years. Each has been delivered from the foreign rule of another by the other's friendship and courage. Our two revolutions helped define the meaning of democracy and freedom which are so much contested in the world today. Today, here in this Gallery, in front of this great painting, we are renewing our commitment to those ideals which have proved such a strong link through so many hazards.

Malraux was especially complimentary of the treatment Americans gave the most beloved painting in the world.

“When upon my return (to France), some peevish spirits will ask me on the rostrum, ‘Why was The "Mona Lisa" lent to The United States?’ I shall answer: ‘because no other nation would have received her like the United States.’”

While America did welcome the "Mona Lisa" very enthusiastically, Malraux made sure to specifically thank the one American who pushed for the loan more than any other: Jackie Kennedy. He said she was “always present when art, the United States, and my country are linked.” He wasn’t lying.

The next day, when the painting was first shown to the public (sitting in a gallery with no other artwork, mounted on a temporary wall in a shatter proof glass case similar to its home in the Louvre), the Washington Post reported that 2,800 people came in the first hour, allowing each one of them a four second look at the masterpiece. The painting hosted 12,000 people on its first day. At the height of "Mona Lisa" Mania, more than 36,000 people visited the Gallery. In fact, the Post’s Rasa Gustatis noted that many people sprinted past Rembrandts when they were let in. On her last day in Washington, the painting nearly doubled the largest crowd that had come out to see King Tut – 53,434.

Two million total people would see her between her stays at the Gallery and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. She would head back to Paris in early March, unscathed, riding in another first class suite. The only other modern loaning of the "Mona Lisa" was in 1974, when France loaned her to museums in Tokyo and Moscow.

Check out this newsreel covering “Mona Lisa’s” American debut.