The Game That Nearly Killed Football

Harvard, Yale, and the collision of Gilded Age morals with America's insatiable thirst for football.

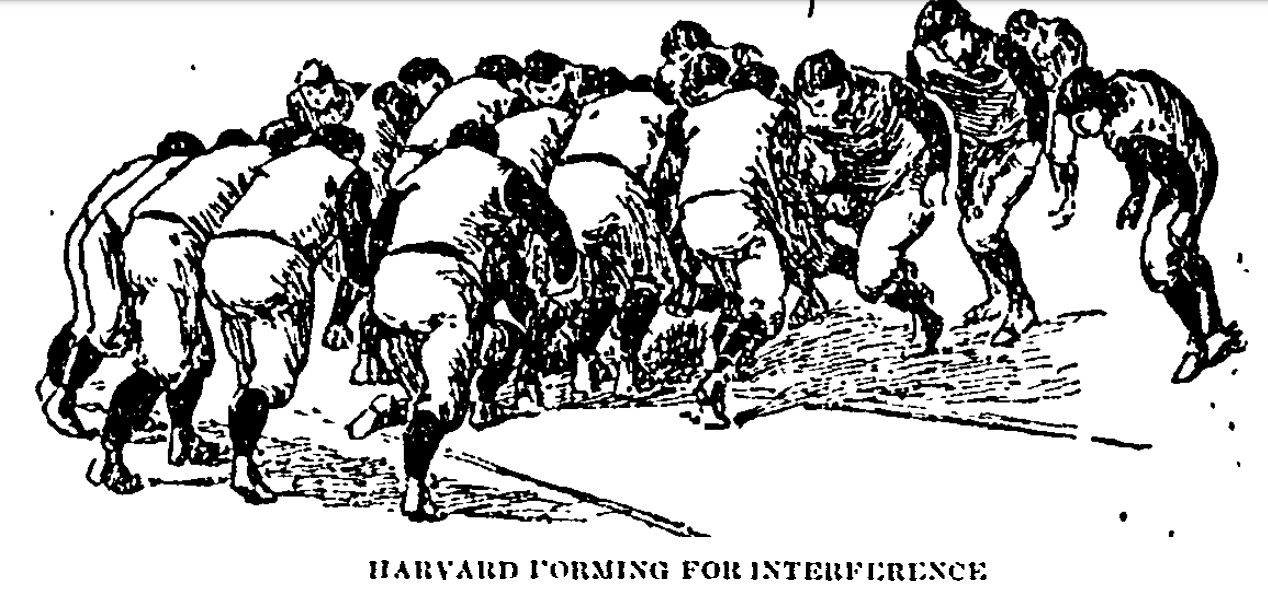

It’s somewhat unsurprising that in the aftermath of the Civil War, the game of football was first developed and began to spread to college campuses nationwide. With the war over, how else would America’s young men test out their manliness? At least, that was the prevailing thought among Walter Camp and other pioneers of the game. At the time, the logic was sound. Football at the time was a test of strength and will, not skill. The first intercollegiate contest between Rutgers and Princeton ended with a final score of 6-4. Players were not allowed to pass the ball forward, and there was no neutral zone at the line of scrimmage, making for some absolutely heinous collisions. There was no real safety equipment to speak of.

In a June 1893 speech delivered to Harvard’s Phi Beta Kappa Fraternity, MIT’s President Francis A. Walker, a former Union General, extolled the value of football to a very receptive audience.

“I am disposed, however, to believe that there has been much exaggeration in the public mind regarding this matter, and that the instances of permanent injury from athletics are much fewer than popular rumor or maternal anxiety makes them to be.”

While the “test of manliness” the games founders envisioned was definitely violent enough and carried with it the possibility of severe injury or death, it actually found itself struggling against its first and fiercest opponent: Gilded Age Sensibilities.

This was a time period where American popular culture – especially among the wealthy (the types of families who could afford to send their sons to prestigious universities) – was dominated by Victorian England and the barbarism of early football was too much for many to bear. The era of debutante balls, cigars rolled in hundred dollar bills, and the “City Beautiful” Movement didn’t mesh well with a sport that produced collisions, bloody noses, broken bones, and sometimes death.

One of the great early opponents of football was one of the men who had the power to derail it – Harvard’s President Charles William Elliot, who served in the role from 1869-1909. Concerned (rightfully so) for the safety of his students, he laid out a plan in February of 1894 to reform what he described as the “evils” of college athletics. His ideas were listed in the Boston Daily Globe on February 25th.

There shall be no Freshman intercollegiate matches or races.

No games, intercollegiate or other, or other, should be played on any but college fields, belonging to one of the competitors, in college towns.

No professional student should take part in any intercollegiate contest.

No student should be a member of a university team or crew in more than one sport within the same year.

No football should be played until the rules are amended so as to diminish the number of and the violence of the collisions of the players, and to provide for the enforcement of the rules.

Intercollegiate contests in any one sport should not take place oftener than once every other year.

Those are massive rules changes, but perhaps the most radical suggestion described in the article was Eliot’s idea that, “If trial shall prove the insufficiency of all these limitations intercollegiate contests ought to be abolished altogether.”

Imagine – a world without football. If Eliot had his way, it’s plausible to imagine that would’ve been the case. The same article made it clear that Brown was the only university in lockstep with Eliot’s ideas. Yale was skeptical. Professor Eugene L. Richards, who was considered the University’s top voice on athletic reform, reacted in a lukewarm fashion.

“Looking over these suggestions it seems as though pres Eliot has not consulted with expert athletes to gain practical advice before getting up these rules. He apparently has been influenced by men who are overhostile to football, and who are not thoroughly acquainted with collegiate athletic programs.”

In a cruel bit of irony, the two schools, each with their own thoughts on the game, would square off in one of the most high profile football games in American history to that point just nine months after Eliot’s report. The results would be disastrous for the game and have many calling for the abolition of football entirely.

The 1894 Harvard-Yale game to be played in neutral Springfield, MA was as highly anticipated a football game as there had ever been. Two of the country’s preeminent universities locking up on the field in any sport was always exciting, but the perception of football as war-like and a “test” made the lead up to this game even more spectacular, and the sport had grown exponentially in popularity since their initial 1875 meeting. This was also the first time the schools faced each other since Eliot’s proposals for possibly banning football were outlined (and since Yale rebuked them).

As the Boston Daily Globe stated in their full front page spread dedicated to the game on November 25th, 1894, Hampden Park in Springfield was overflowing with more than 23,000 spectators, including “10,000 sons of fair Harvard [screaming] frantic shouts of encouragement to the boys from Cambridge.”

It was a festive atmosphere for sure, trainloads of people coming from New Haven and Cambridge were dropped at the neutral site to see the game in person, and the media covered it from every angle. The Globe even ran a column by Grace Parker called “From a Woman’s Standpoint” in which they sent a woman who had never seen a football game to report back on her thoughts. She started off with the fortuitous observation that “Football is not a craze, it is a passion.”

The game itself was a 12-4 victory for Yale. That’s possibly the least significant result of what happened that day, however. This meeting, the most covered and attended football game in history to that point – was a bloodbath. On the front page, a Globe headline screamed:

“Game At Times Was Rough, and Many Men Were Injured, Murphy of Yale Seriously – Dr. Brooks Says That a Severe Blow Has Been Dealt to the College Sport Unless Radical Action is Taken.”

Not ideal.

The attitude towards injuries was very different in the 1890s than in modern times. For example, the Globe noted that Yale’s fullback, named Butterworth, “Was struck in the head, and undoubtedly was of little assistance for the rest of the time that he tried to play. He seemed to be completely dazed. He was not allowed to punt the ball once and when he ran he had very little force, seldom making a gain.”

Butterworth’s injury was minor in comparison with Yale tackle Fred Murphy’s. According to the account of the game, he was “knocked senseless” in the first half, to the point that “He did not even know which was his goal, and between each two plays had to have the situation explained to him.”

As was customary, Murphy attempted to play the second half, but his body couldn’t bear it. He collapsed unconscious and was carried off the field, and by the time the story was sent in later that night, he hadn’t regained consciousness. There were broken legs, broken collarbones, and black eyes all over. By the estimation of The New York Times, more than five players needed to be hospitalized after the game. There were rumors around Springfield that Murphy had died, but he did eventually recover.

Even in the hours immediately following the game, there was a sense that what took place at Hampden Park could have negative ramifications for the game as a whole. Reporters noted that the Harvard-Yale game had been clean for years before that day, but that “To the shame of both elevens it can be said that the exhibition of unnecessarily rough and brutal playing they gave at times today will have an important bearing on their future relations in football.”

“It is inevitable that what took place today should create no end of discussion as to whether the game should be continued or not.”

In fact, the game did not continue in 1895 or 1896. This was the direct result of the outcry stemming from the shocking matchup. It was the exact sort of ammunition Eliot and other reformers needed to justify their anti-football mindsets. It would take lobbying and great public relations to convince upper class Americans that football was something their sons should be doing. The rules changes enacted in 1906 – such as legalizing the forward pass and establishing a neutral zone – were critical in making the game safer. However, the debate about football remains alive to this day.